With extreme weather events impacting cities around the world and urban population growth contributing to increased flooding potential, the field of stormwater management has grown more complex in recent years. Infrastructure designers have seen many of their trusted design methods riddled with uncertainty as stormwater systems are overtaxed by flood events and government agencies seek to better protect the public.

Fortunately for designers and owners of stormwater systems, recent technology advancements provide new ways to model storms and design systems to handle those events. A large wave of federal funding has also enabled U.S. agencies to invest heavily in major infrastructure improvements. Questions still remain about how much to change current design approaches, but designers have a plethora of tools available to address the challenges they face.

Image source JJ Gouin/stock.adobe.com.

North Carolina City Digs In

After Fayetteville, N.C., was hit with major storms four years in a row — Matthew (2016), Irma (2017), Florence (2018), and Dorian (2019) — city leaders called for change. The city had been performing small-scale drainage improvements, but the catastrophic events prompted Fayetteville to accelerate efforts and undertake more comprehensive watershed studies.

Assisted by a team of consultants led by Freese and Nichols, the city of Fayetteville created a stormwater geodatabase to assist with long-term planning and system performance evaluation. The team assimilated existing information and translated it into an Esri geodatabase format to provide a uniform data framework. With the city extending across 100 square miles and 15 watersheds, the team used a variety of tools to complete the studies — the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers HEC-HMS for overall hydrology of watersheds, HEC-RAS for primary system hydraulics, and Autodesk InfoWorks ICM for detailed analysis and visualization of sub-basins inundated during various storm events.

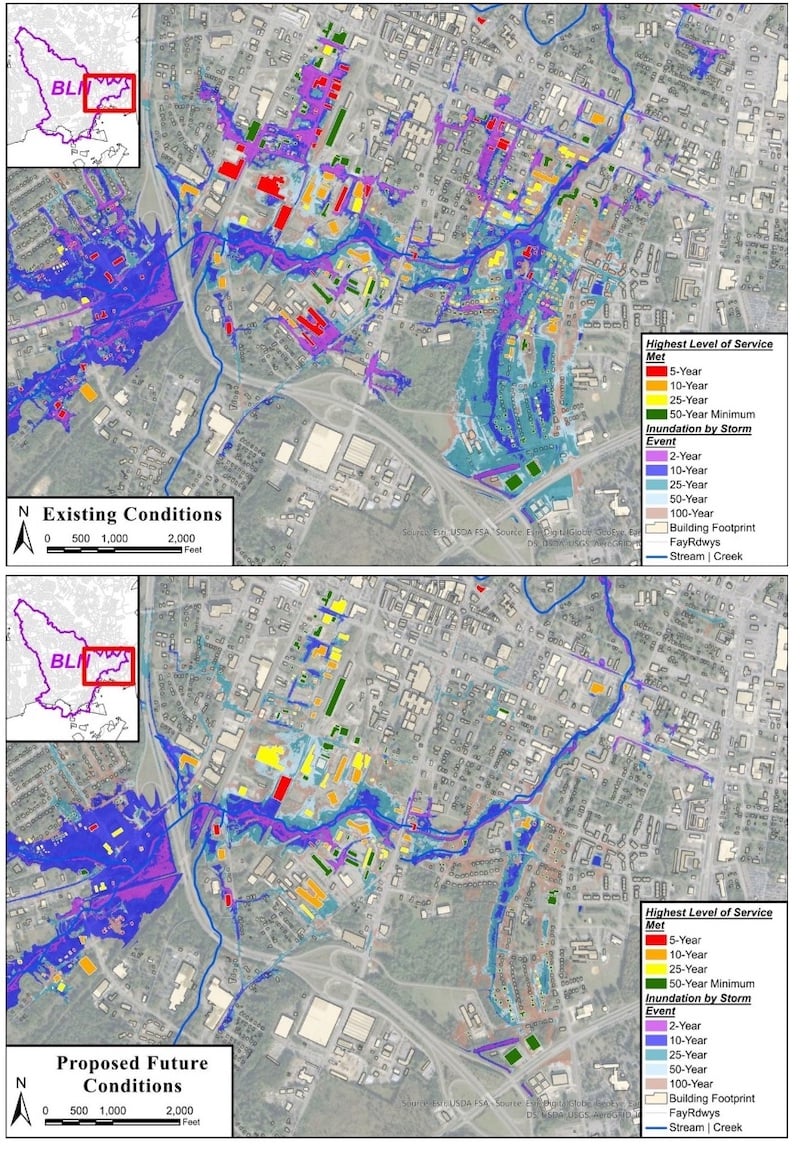

Using InfoWorks, the team created maps of existing conditions and proposed conditions that incorporated future improvements. The maps highlighted a range of storms from 2- to 100-year events. Based on the studies, the city prioritized a series of improvements, including extending four bridge sections and enlarging a floodplain as part of the Russell-Person St. Bridges and Stream Enhancement. The solution also helped reduce potential flood impacts in 10 other areas.

The Fayetteville team used Autodesk's InfoWorks ICM to create maps showing existing and proposed conditions for various storm events. Image source: Autodesk.

The Fayetteville team used Autodesk's InfoWorks ICM to create maps showing existing and proposed conditions for various storm events. Image source: Autodesk.

“By using InfoWorks ICM in coordination with other hydraulic and hydrologic software such as HEC-RAS and HEC-HMS, we were able to precisely measure all of our project goals and prove — without a doubt — that our watershed planning would deliver positive outcomes for the community,” said Fayetteville public services director Sheila Thomas-Ambat.

The Fayetteville improvements also met key social equity requirements for federal funding, such as the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities (BRIC) program. All benefitting census tracts of the project met Justice-40 criteria, and all but one had CDC Social Vulnerability Index (SVI) scores above 0.93, meaning 93% of tracts in the area considered are less vulnerable than the tract of interest.

Improvements in Fayetteville highlight a broader need for new approaches to modeling stormwater systems, according to David Totman, director of infrastructure industry strategy at Autodesk. “Historical stormwater management perspectives are being challenged and need to be modernized,” he noted. While watershed modeling has traditionally used a one-dimensional (1D) approach that assumes flow is contained within a defined channel or conduit, more accurate 2D modeling better represents water moving in multiple directions.

Totman also said water quality needs to be evaluated along with quantity. “We need to look at nutrients being washed across watersheds and ending up in our water bodies. The quality aspect needs to be in the conversation [when performing stormwater management],” he noted.

Extending technology further, Autodesk recently introduced Machine Learning Deluge, an AI-based tool that helps predict flood conditions more quickly and accurately when applying water on a site surface. A subset of Autodesk’s InfoDrainage, MLD uses AI algorithms to analyze flooding conditions and present potential locations for storage structures and stormwater controls. “It helps us understand patterns and where water will go,” said Totman. “It can expedite the entire design process.”

Combining 1D and 2D Modeling

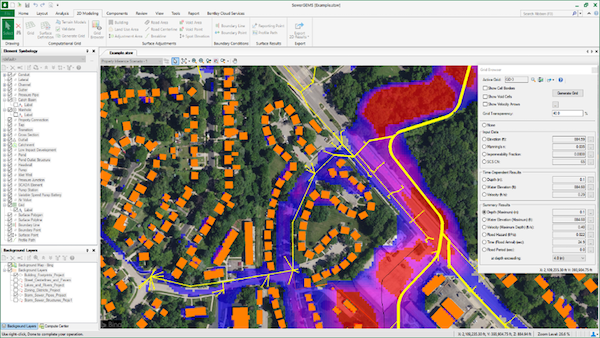

In some cases, a combination of 1D and 2D modeling can be effective in analyzing multi-faceted stormwater systems. “Linking 1D and 2D models integrate hydraulic modeling of surface (2D overland) flows with the 1D elements in sewers, stormwater inlets, detention facilities, and other elements to provide a more detailed picture of flooding extent and impact,” said Sandra DiMatteo, industry marketing director for water infrastructure at Bentley Systems, Inc.

Bentley’s OpenFlows Storm software has been used to help cities improve resilience against flooding, according to DiMatteo. OpenFlows Storm includes StormCAD, CivilStorm, and PondPack software for modeling and analyzing 1D elements, such as gutters, channels and pipes. In recent years, Bentley added system modeling for 2D overland flow.

The need for more detailed modeling has become more pronounced with the increase in extreme weather events in many places around the world, along with increased urbanization, noted DiMatteo. “These factors put pressure on existing stormwater systems,” she said. “Modeling plays a key role in making the best decisions and mitigating risk in today’s volatile climate.”

Another issue facing cities is unintended inflows into sewer networks. When stormwater system capacities are exceeded, overflows can enter sanitary sewer systems, reducing wastewater system capacities and potentially polluting downstream water bodies. With applications such as Bentley’s OpenFlows SewerGems, utilities can model their network through different scenarios and alternatives and perform integrated analyses that consider network sensor data, guiding decisions on where to make improvements, noted DiMatteo.

Bentley’s SewerGEMS can be used to model different stormwater scenarios. Image source: Bentley Systems, Inc.

Consultants Embrace New Technology

Stormwater engineering consultants have been leveraging the new technology to perform more precise design and analysis than in the past. Bob Steele, a senior hydrology and hydraulics designer and modeler at Infrastructure Consulting & Engineering, LLC, in West Columbia, SC, says the current tools have enabled more accurate modeling to be done in far less time than previous modeling efforts.

“The biggest improvement is going from old static software to new dynamic software,” he said. “You can use hydrograph methods and work with a varying Q [flow rate] instead of a static Q,” Steele said. This enables designers to better model features such as detention ponds, rain gardens, and in-line storage of stormwater in pipes and structures. ICE has used a variety of tools for stormwater analysis, including Bentley’s Sewer GEMS, StormCAD, and CivilStorm, along with the Corps’ HEC software, and TuFlow from BMT Commercial Australia Pty Ltd.

Josh Eisenoff, a project engineer with Quattrone & Associates, Inc., in Fort Myers, FL, has seen increased storm intensities and rising water table levels affect regional design practices. Most of his firm’s projects are subject to design criteria of the South Florida Water Management District, which requires that minimum parking lot elevations meet or exceed the 5-year, 24-hour storm event. Due to recently observed changes in weather patterns, his firm has been designing parking lot elevations to the 10-year, 24-hour storm while the watershed district evaluates potential updates to their design guidelines and criteria.

“Increased water tables coupled with higher intensity storm events are causing sites to be built higher and higher in elevation,” said Eisenoff. His firm primarily uses StormWise (formerly ICPR4) from Streamline Technologies to determine design elevations and Bentley’s StormCAD for pipe sizing.

Virginia-based Dewberry, which provides infrastructure planning and design, as well as ongoing support on FEMA’s National Flood Insurance Program, is seeing recent weather patterns affect the design of infrastructure and coastal projects, according to Rahul Parab, water department manager for Dewberry’s New York City office. “Higher intensity rainfall and higher rainfall depths result in incremental increases in infrastructure sizes,” he said.

To more thoroughly model flood conditions, Dewberry often considers multiple storm events to see how proposed infrastructure will perform, and whether larger pipes, detention capacities, or outlet control structures are warranted. Along with the hydraulic analyses, the firm also often performs benefit-cost analyses to prove the effectiveness of various infrastructure components. Dewberry uses the Corps’ HEC software, along with the EPA’s SWMM, Autodesk’s InfoWorks ICM, the Danish Hydraulic Institute’s MIKE, and other tools.

Re-examining Methodologies

With the increased focus on weather patterns, government agencies are reviewing potential changes to design criteria and methods. The National Weather Service (NWS), which is part of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), has published an authoritative atlas of precipitation-frequency estimates, most recently as NOAA Atlas 14. These estimates are based on historical rainfall data and are used widely across the U.S. to design, plan, and manage much of the nation’s public infrastructure.

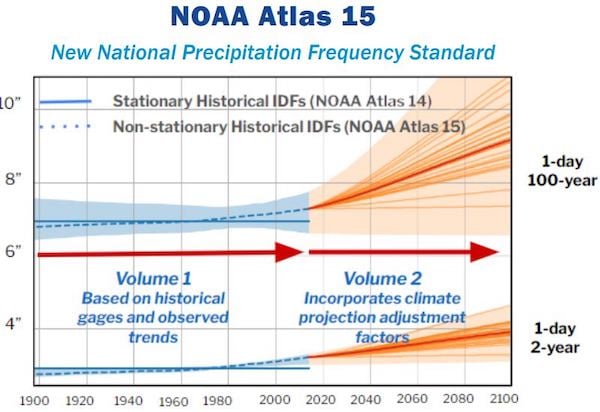

The 2022 Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) provided new funding to update the estimates and publish a new Atlas 15 in two volumes. Volume 1 will account for temporal trends in historical observations, and Volume 2 will use future climate model projections to generate adjustment factors for Volume 1.

NOAA Atlas 15 will include both historical and projected precipitation data. Image source: National Weather Service.

Dewberry’s Parab says the use of both historical and projected precipitation data is a sound approach for designers. “Rainfall intensity and duration is changing. It's time to recognize that,” he said.

While the AEC community is likely to accept the new approach, other questions remain about current and future stormwater design practices. Mike Meadows, an associate professor of civil and environmental engineering at the University of South Carolina, says design methodologies needed revamping long before recent weather patterns became the focus.

Many designers have used the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) unit hydrograph method to design stormwater facilities, a method with limited flexibility to adapt to different watershed characteristics. Meadows cites watershed characteristics such as area, hydraulic length, slope, land use, and soils that vary widely and are not well represented by NRCS parameters such as a single curve number (CN) and 24-hour storm durations. As such, many designers undersize ponds and oversize outflow structures, according to Meadows.

“Watersheds are like people,” Meadows wrote in a recent presentation. “People have different personalities and so do watersheds.” Based on his research, he has developed the South Carolina Synthetic Unit Hydrograph Method that uses modified CN values for shorter duration events and adjusts other parameters such as the peak rate factor (PRF) and time of concentration to more accurately reflect watershed characteristics. While not specifically part of his research, he believes storm intensities in his region have been increasing in recent years.

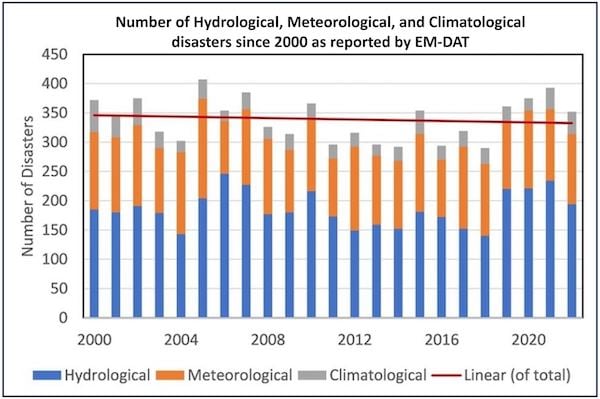

Other technical sources question the validity of using projected increases in storm intensities for design purposes, as proposed by NOAA. Dr. Matthew Wielicki, an independent science reporter and former assistant professor of earth science at the University of Alabama, cites data from the Emergency Events Database (EM-DAT) that shows no overall increase in hydrological, meteorological, and climatological disasters since 2000. The revised NOAA approach to use projected increases in storm intensity is based on uncertain assumptions regarding climate change, according to Wielicki.

EM-DAT data shows no overall increase in hydrological, meteorological, and climatological disasters since 2000. Image source: Dr. Matthew Wielicki.

“I think that this assumes that rain patterns would be stable without human influence, which is not what we see in the geologic record,” said Wielicki. “Places like California, for example, have had major droughts and wet periods long before anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions, and we should expect that to happen again. It's very difficult to untangle natural variation from human influence.”

Sorting it all Out

Regardless of viewpoints on climatological data, the bottom line for stormwater designers is that the landscape is changing. Simplistic design methods of the past are being replaced by more sophisticated modeling techniques, and owners are seeking more resilient systems. Designers will need a variety of tools in the toolbox to analyze and design stormwater systems of the future.

Andrew G. Roe

Cadalyst contributing editor Andrew G. Roe is a registered civil engineer and president of AGR Associates. He is author of Using Visual Basic with AutoCAD, published by Autodesk Press. He can be reached at editors@cadalyst.com.

View All Articles

Share This Post